Nearly all of Phnom Penh’s communes have voter registration rates in excess of 100 per cent, amounting to more than 145,000 additional names, with one commune topping the 200 per cent mark, an analysis of previously unseen government population data reveals.

Further analysis of the already public National Election Committee voter list shows there are more than 25,000 exact duplicate names in Phnom Penh alone, despite previous NEC assurances that exact duplicates had been removed.

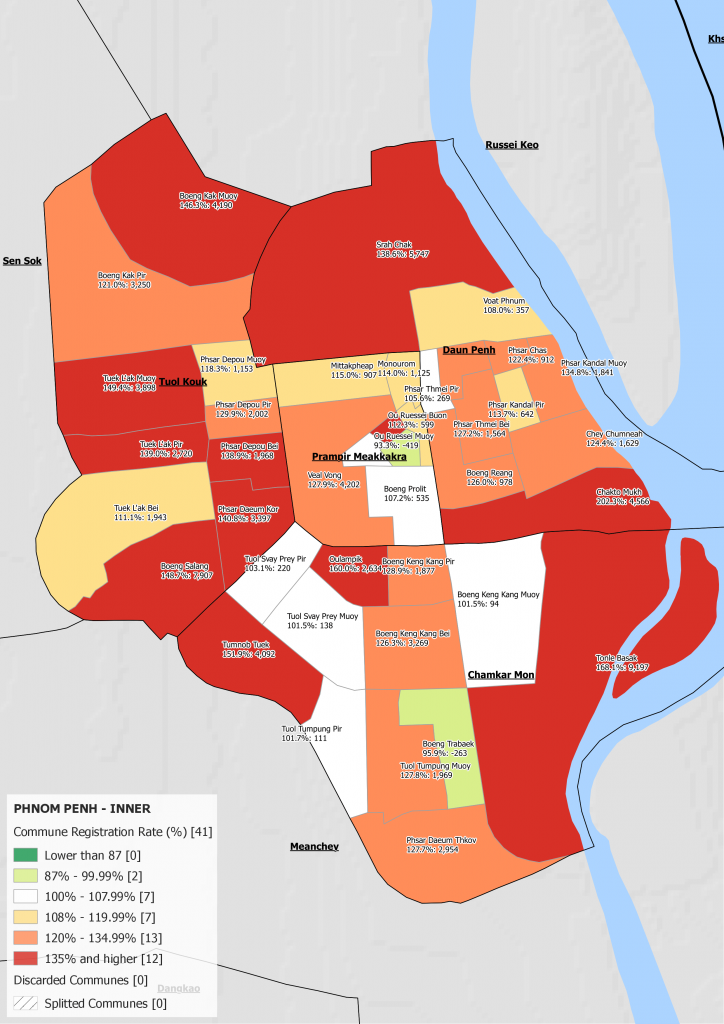

That data as well as leaked commune-level numbers obtained by the Post draw detailed maps of over-registration.

These bloated registration rates raise concerns that ballot rigging could be conducted in specific areas through various methods, from more sophisticated manipulation of voter identity documents to simple ballot stuffing.

The huge spike of names in Phnom Penh, where 83 out of 96 communes have more than 100 per cent registration, is repeated in key electoral provinces across the country. In Kampong Cham, a total of about 129,000 more voters than people of voting age are registered in 137 of 173 communes.

For battleground provinces Kandal and Prey Veng, the number of excess voters in 122 of 127 communes totals more than 114,000 and 64,000 in 96 of 116 communes, respectively.

In some cases, comparisons of the late 2012 NEC voter registration list and the government-produced, UNDP-sponsored commune/sangkat database (CDB) reveal there are as many as 9,000 additional registered voters across individual communes.

One of the major concerns to monitors is that the NEC has issued an unusually high number of Identification Certificate for Election (ICE) forms — nearly 500,000 — after the voter-registration period closed late last year. Election watchdogs have warned that these forms can be easily misused to claim excess names.

Laura Thornton, resident director of the National Democratic Institute, said the fact that there were “way too many” names on the voter list, direct duplicates and an unusually high number of ICEs all amounted to “a concerning cocktail of information”.

“The concern is that if you have a bunch of extra names on the voter list that you want to take advantage of, an easy way would have been to get an ICE issued in the name of a duplicate name,” she said.

“So if a party wanted to use names, that would be the easiest way to do it.”

Though ICE forms were used legitimately to register people to the voter list, Thornton explained that the only legal use for the hundreds of thousands that had been issued after registration was in the rare event that some lost their identification through theft or bad luck.

“To think that [so many] people would need that, it’s just not plausible,” she said.

Another way the additional names could be exploited was if polling officials simply did not check IDs, though this was considerably more risky because, unlike ICEs, such actions could be spotted by polling monitors.

“What will be fascinating to see will be … what happens on Election Day, what is the turnout in those areas and how many people will vote with ICEs.”

Provided the applicant has two witnesses and photos, ICEs can be approved by commune chiefs — more than 97 per cent of whom belong to the ruling Cambodian People’s Party.

NEC secretary-general Tep Nytha maintained the high number of ICEs issued since registration was required to account for all of those who might have lost their ID.

“We have issued 480,000 ICEs since registration to vote [ended]. From January to this time, we are totalling it and will have a number tomorrow,” he said yesterday.

Nytha said the NEC had cleaned many duplicated names from the voter list, though some had not been cleared because slight variations in spelling could make identification difficult.

But he declined to specifically address questions about direct duplicates in Phnom Penh and said he would have to look into figures of over-registration before commenting.

The highest rates of over-registration coincide with two things: the provinces that are worth the highest number of seats at the election and the provinces in which the opposition are considered to have the greatest chance of making inroads. In safe CPP rural provinces, the over-registration rate is far lower.

By sheer number of names registered above the government CDB population figures, communes in Phnom Penh stand out, with Toek Thla commune in Sen Sok district at 9,472 (136.9 per cent) and Tonle Bassac commune in Chamkarmon district at 9,197 (168.0 per cent).

The highest percentages of over over-registration, meanwhile, are found in Chang Krang commune in Kratie province’s Chet Borei district (209.5 per cent) and at Chaktomuk commune in Phnom Penh’s Daun Penh district (202.3 per cent).

But it is inner Phnom Penh that is most disturbing as a whole. There, 12 of 41 communes have an over-registration rate above 135 per cent. In these inner-city communes, the opposition fared above-average.

A total 25,251 voters registered on the NEC list for Phnom Penh, meanwhile, have exactly the same name with the same spelling, same date of birth and same gender.

In a statement issued in April, the NEC announced that “for double names which were found on the 2011 voters lists by Comfrel … NEC did not completely delete because the NEC deleted only the names which have the same data.”

Cambodia National Rescue Party candidate Son Chhay said his party had found instances where one person’s name had been repeated on the voter list up to seven times and that the same tactics had stopped the opposition from winning a single commune chief position in Phnom Penh in the 2012 commune election.

“This success gave them [the CPP] another idea, that they will do the same for this election so they increase the number of extra voters,” he said.

“This is the thing that we are very concerned about right now.”

Sam Rainsy Party senator Mardi Seng said he was shocked to hear how high the rates were but was, at least anecdotally, well aware of the problem.

“I’m one of them. I’ve found my name in two different communes, and I am very interested in who is voting for me in the other place.”

ADDITIONAL REPORTING BY MEAS SOKCHEA